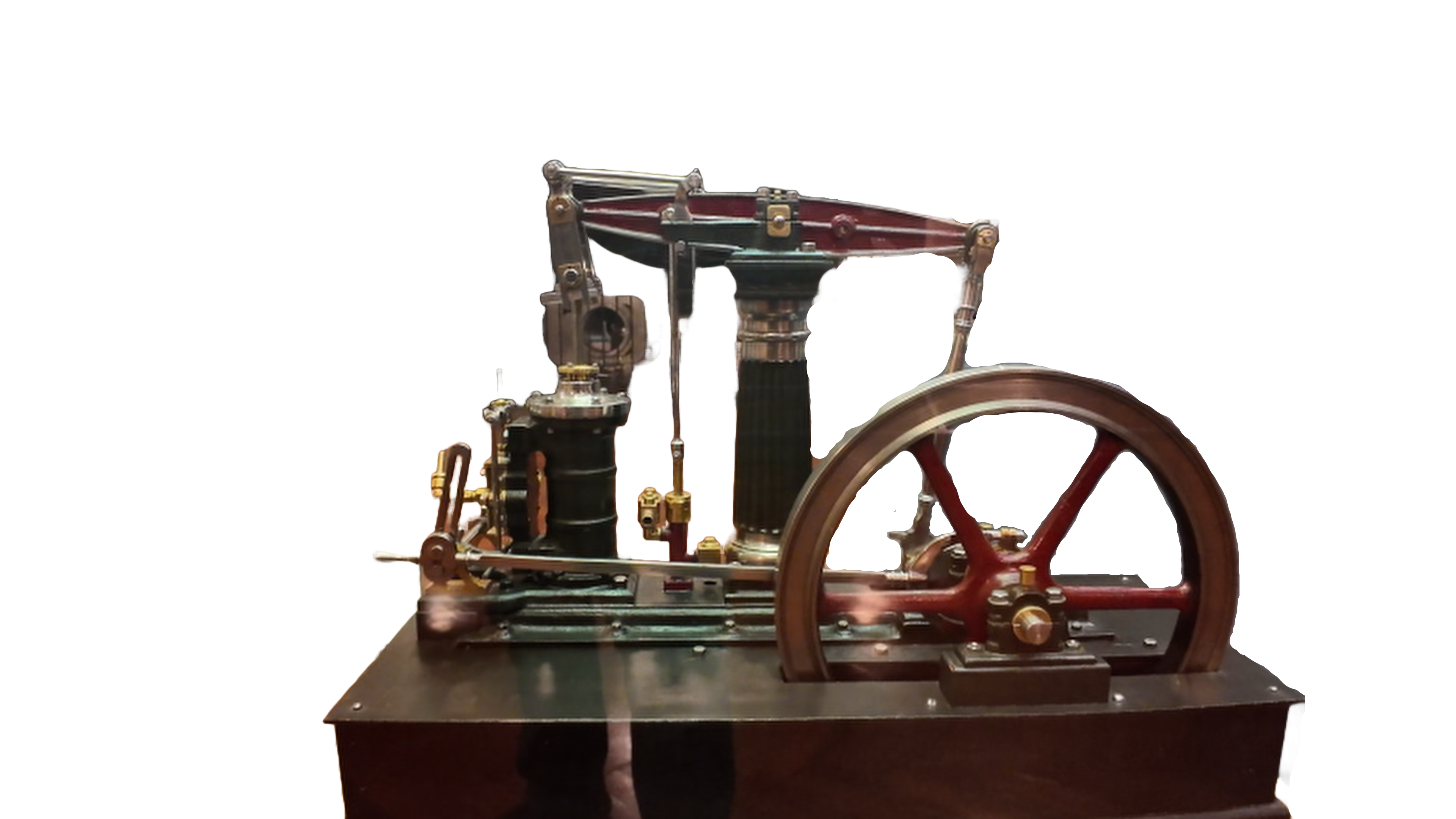

Need a steam engine at home?

Wonder what camera I use?

By using the Industrial Revolution store, you can buy Industrial Revolution-related models and equipment, and help out the Industrial Revolution Channel at the same time.